This blog aims to summarize everything about the javascript-specific vulnerability - prototype pollution: necessary knowledge about javascript, what is the prototype and prototype chain, how to exploit the prototype pollution vulnerability and several CTF challenges related to the prototype pollution which might help in understanding all the stuff.

1 Something about JavaScript

For a beginner in Javascript, I strongly recommend the following learning material to you.

https://javascript.info/getting-started

I think this kind of website, with well-organized structure and code examples, might help you learn the language step by step. However, I just keep the important points and something I don't know before below as a reminder.

1.1 javascript runtime

What kind of language is javascript? Compiled vs. Interpreted

Because I am taking a compiler and interpreter course this semester, I'd like to talk about this question. I think the most accurate way to distinguish between a compiled language and an interpreted language is whether we rely on an engine(Interpreter) to run the program.

For the compiled language like C, it would be compiled into a source code file written in assembly language and further be translated to machine code and output an object file by an assembler. An object file is written in the lower-level language and has the necessary format (ELF for Linux) to be running on every machine with the same instruction set. So the biggest advantage of compiled languages is Fast because you don't need to compile while running the program and you can do several optimizations while translating the source code(IR) to assembly.

For the interpreted language like Python, its advantage is portability and convenience. There is only one step to get from the source code to execution which is putting your code on a virtual machine. So if you got a virtual machine(interpreter), you can run the script no matter what computer you are using.

Someone would argue that javascript is not an interpreted language due to the introduction of JIT(just-in-time Compiler) for js. However, the JIT compiler just enables us to optimize the code part while running. It usually contains a monitor or profiler to keep track of how many times the different statements are executed and detect which parts of your code are being used the most, and then it’ll send them over to be compiled and stored. And the warm sections of your code will be compiled into bytecode, which in turn, is run by an interpreter that is optimized for that type of code. It draws on the advantages of compiled languages, but it is still an interpreted language moving a bit forward in the middle.

Where does javascript run?

Usually, we see javascript on both client-side and server-side. The client-side javascript is often used for rendering the pages as well as making pages interactive. On the client side, the browsers take care of our javascript code and run it on their javascript engines like v8 on Google Chrome, spidermonkey on Mozilla Firefox, and chakra on IE. The server-side javascript is often used for handling the requests and giving responses. On the server side, we use Node.js which is built on Chrome's V8 JavaScript engine. I consider all of them as javascript interpreters with libraries that contain core modules like File System, HTTP, Events, etc.

1.2 javascript variables and data types

var, let, and const

let– is a modern variable declaration.var– is an old-school variable declaration.const– is likelet, but the value of the variable can’t be changed, as for const value.

let and var basically do the same things, so use let instead.

data types in javascript

There are eight basic data types in JavaScript.

- Seven primitive data types (primitive stands for their values contain only a single thing (be it a string or a number or whatever):

numberfor numbers of any kind: integer or floating-point, integers are limited by±(253-1).bigintfor integer numbers of arbitrary length.stringfor strings. A string may have zero or more characters, there’s no separate single-character type.booleanfortrue/false.nullfor unknown values – a standalone type that has a single valuenull.undefinedfor unassigned values – a standalone type that has a single valueundefined.symbolused to create unique identifiers for objects

- And one non-primitive data type:

objectfor more complex data structures, which we will cover later.

1.3 javascript functions

There are three ways to create a function in JavaScript:

Function Declaration: the function in the main code flow

function sum(a, b) { let result = a + b; return result; }Function Expression: the function in the context of an expression

let sum = function(a, b) { let result = a + b; return result; };Arrow functions:

// expression on the right side let sum = (a, b) => a + b; // or multi-line syntax with { ... }, need return here: let sum = (a, b) => { // ... return a + b; } // without arguments let sayHi = () => alert("Hello"); // with a single argument let double = n => n * 2;

Besides the coding way, the more subtle difference is when a function is created by the JavaScript engine.

A Function Expression is created when the execution reaches it and is usable only from that moment. Once the execution flow passes to the right side of the assignment let sum = function… – here we go, the function is created and can be used (assigned, called, etc. ) from now on.

A Function Declaration can be called earlier than it is defined.

For example, a global Function Declaration is visible in the whole script, no matter where it is. That’s due to internal algorithms. When JavaScript prepares to run the script, it first looks for global Function Declarations in it and creates the functions. We can think of it as an “initialization stage”.

And after all Function Declarations are processed, the code is executed. So it has access to these functions.

Function is a value

Let’s reiterate: no matter how the function is created, a function is a value. Both examples above store a function in the sayHi variable.

We can even print out that value using alert:

function sayHi() {

alert( "Hello" );

}

alert( sayHi ); // shows the function codePlease note that the last line does not run the function because there are no parentheses after sayHi. There are programming languages where any mention of a function name causes its execution, but JavaScript is not like that.

In JavaScript, a function is a value, so we can deal with it as a value. The code above shows its string representation, which is the source code.

Surely, a function is a special value, in the sense that we can call it like sayHi().

But it’s still a value. So we can work with it like with other kinds of values.

We can copy a function to another variable:

function sayHi() { // (1) create

alert( "Hello" );

}

let func = sayHi; // (2) copy

func(); // Hello // (3) run the copy (it works)!

sayHi(); // Hello // this still works too (why wouldn't it)Here’s what happens above in detail:

- The Function Declaration

(1)creates the function and puts it into the variable namedsayHi. - Line

(2)copies it into the variablefunc. Please note again: there are no parentheses aftersayHi. If there were, thenfunc = sayHi()would write the result of the callsayHi()intofunc, not the functionsayHiitself. - Now the function can be called as both

sayHi()andfunc().

1.4 javascript objects

The interesting Object

Objects are used to store keyed collections of various data and more complex entities. The reason why we are always talking about that the javascript language is the most dynamic language can be shown as follows.

First of all, let's define an object. It should be noted that the object stores properties in the form of key-value pairs, and the keys must be strings or symbols and the values can be of any type.

let user = { // an object

name: "John", // by key "name" store value "John"

age: 30 // by key "age" store value 30

"likes birds": true // quoted string as a key

};And we can use the following way(square brackets or dots)to get the properties of a defined object.

console.log(user.name) //john

console.log(user.age) //30

console.log(user['like birds']) // trueOr we can add an unexisting property to an object or delete an object's property.

console.log(user["whoami"]=user.name) // user.whoami = "John"

delete user.age // delete the age propertyDue to the great flexibility of javascript, we can also access an object's properties by variables.

let key = prompt("What do you want to know about the user?", "name");

let key = "name" // an alternative way

// access by variable

alert( user[key] ); // John (if enter "name")

// However, dot is not allowed.

let key = "name";

alert( user.key ) // undefinedLet's go further. The property name of an object can be a variable and be computed.

let fruit = prompt("Which fruit to buy?", "apple"); //user input

let bag = {

[fruit]: 5, // the name of the property is taken from the variable fruit

};

// take property name from the fruit variable

bag[fruit] = 5; // the same as bag["hello"] if the user input is helloAnother interesting thing is that we can also use the variable to add a property to an object.

let fruit = prompt("Which fruit to buy?", "apple");

let bag = {};

// take property name from the fruit variable

bag[fruit] = 5;Above all, we can understand that the most important data type, Object, is so dynamic and flexible together with variables.

Object references and copying

One of the fundamental differences between objects versus primitives is that objects are stored and copied “by reference”. In contrast, primitive values: strings, numbers, booleans, etc – are always copied “as a whole value”.

For the primitive values:

let message = "Hello!";

let phrase = message; // coping a phrase

//let's change one of them

phrase = "Bye"

console.log(message) // print Hello!However, for the object:

let user = {

name: "John"

};

let user2 = user // coping an object

//let's change one of them

user2.name = "Jack"

console.log(user.name) // print JackFor the advanced data type, for example objects, we can use == or === to compare their reference.(However, for the primitive variables, == is used to compare the values between different data types, and === is used to compare the values between the same data types.)

let user = {}

let user2 = {}

let user3 = user

console.log(user === user2) // True

console.log(user === user3) // TrueObject method: this

if you consider this keyword as a dynamic pointer to an object, it should be easy to understand the following part.

A function that is a property of an object is called its method.

let user = {

name: "John",

age: 30

};

user.sayHi = function() {

alert("Hello!");

};

user.sayHi(); Also, we can define a function in an OPP(Object-oriented programming) way.

// these objects do the same

user = {

sayHi: function() {

alert("Hello");

}

};

// method shorthand looks better, right?

user = {

sayHi() { // same as "sayHi: function(){...}"

alert("Hello");

}

};What if we want to visit the object's properties inside an object's method? Since we usually do such things in Java or other OPP way with the support of self keyword. So, in javascript, we use this method.

let user = {

name: "John",

age: 30,

sayHi() {

// "this" is the "current object"

alert(this.name);

}

};

user.sayHi(); // JohnOne more thing to note is that this is not bound. The value of this is evaluated during the run-time, depending on the context. The rule is simple: if obj.f() is called, then this is obj during the call of f. This is a simple way to decide which object this is pointing at currently.

Symbols

By specification, only two primitive types may serve as object property keys: string, or symbol type. A symbol represents a unique identifier.

A value of this type can be created using Symbol():

let id = Symbol();

// id is a symbol with the description "id"

let id = Symbol("id");Symbols are guaranteed to be unique. Even if we create many symbols with exactly the same description, they are different values. The description is just a label that doesn’t affect anything.

For instance, here are two symbols with the same description – they are not equal:

let id1 = Symbol("id");

let id2 = Symbol("id");

alert(id1 == id2); // falseSo why is there a Symbol?

Symbols allow us to create “hidden” properties of an object that no other part of the code can accidentally access or overwrite.

let user = { // belongs to another code

name: "John"

};

let id = Symbol("id");

user[id] = 1;

alert( user[id] ); // we can access the data using the symbol as the keyAs user objects belong to another codebase, it’s unsafe to add fields to them since we might affect pre-defined behavior in that other codebase. However, symbols cannot be accessed accidentally. The third-party code won’t be aware of newly defined symbols, so it’s safe to add symbols to the user objects.

2 The inheritance of javascript: Prototype

We are heading for the most exciting part of javascript: Prototype. In this section, we are going to talk about three important concepts: constructor, __proto__([[prototype]]), and prototype.

2.1 constructor and keyword 'new'

The regular {...} syntax allows us to create one object. But often we need to create many similar objects, like multiple users or menu items, and so on.

That can be done using constructor functions and the "new" operator.

function User(name) {

this.name = name;

this.isAdmin = false;

}

let user = new User("Jack");

alert(user.name); // Jack

alert(user.isAdmin); // falseWhen a function is executed with new, it does the following steps:

- A new empty object is created and assigned to

this. - The function body executes. Usually, it modifies

this, and adds new properties to it. - The value of

thisis returned.

The main purpose of constructors is to implement reusable object creation code. By using the User() function, we can then create multiple user without keeping writing the properties inside the User().

Any function could be a constructor if it has been invoked with the keyword new.

Return of a constructor

Usually, constructors do not have a return statement. Their task is to write all the necessary stuff into this, and it automatically becomes the result.

But if there is a return statement, then the rule is simple:

- If

returnis called with an object, then the object is returned instead ofthis. - If

returnis called with a primitive, it’s ignored.

function BigUser() {

this.name = "John";

return { name: "Godzilla" }; // <-- returns this object

}

alert( new BigUser().name ); // Godzilla, got that objectLet me reemphasize that, during this part, if you consider this keyword as a dynamic pointer to an object, it should be easy to understand.

2.2 __proto__ and [[prototype]]

While using the constructor and new keyword, we can construct a lot of instances of an object. This embodies the class and instance concepts in other OOP languages. However, what about inheritance? What if we need to extend the methods and properties of an object?

Every object has hidden and special the __proto__([[prototype]]) property which is a reference to an object called prototype. This prototype object is the object you want to expand and rewrite.

__proto__ or [[prototype]]

They are not exactly the same thing, but they all provide a way to access to the prototype object. The __proto__ property is a bit outdated. So we might take [[prototype]] as the following discussion.

Let's see an example.

let animal = {

eats: true

};

let rabbit = {

jumps: true

};

sets rabbit.[[Prototype]] = animal //rabbit.__proto__ = animal;Here we can say that "animal is the prototype of rabbit" or "rabbit prototypically inherits from animal".

// we can find both properties in rabbit now:

alert( rabbit.eats ); // true (**)

alert( rabbit.jumps ); // trueWhen alert tries to read property rabbit.eats (**), it’s not in rabbit, so JavaScript follows the [[Prototype]] reference and finds it in animal (look from the bottom up).

this keyword in the prototype's fucntion

An interesting question may arise in the example below: what’s the value of this inside set fullName(value)? Where are the properties this.name and this.surname written: into user or admin?

let user = {

name: "John",

surname: "Smith",

set fullName(value) {

[this.name, this.surname] = value.split(" ");

},

get fullName() {

return `${this.name} ${this.surname}`;

}

};

let admin = {

__proto__: user,

isAdmin: true

};

alert(admin.fullName); // John Smith (*)

// setter triggers!

admin.fullName = "Alice Cooper"; // (**)

alert(admin.fullName); // Alice Cooper, state of admin modified

alert(user.fullName); // John Smith, state of user protectedThe answer is simple: this is not affected by prototypes at all.

No matter where the method is found: in an object or its prototype. In a method call, this is always the object before the dot.

2.3 function.prototype

Previously, we could set the prototype of an object by set object.[[prototype]]=object2. However, it would be laborious when we construct a lot of instances of an object and make sure they have the same [[prototype]]. We have learned to use constructor and new keyword to create new objects with the same properties which save a lot of time, so what is their default [[prototype]]?

function User(name) {

this.name = name;

this.isAdmin = false;

}

let user = new User("Jack");

let user2 = new User("Emily");

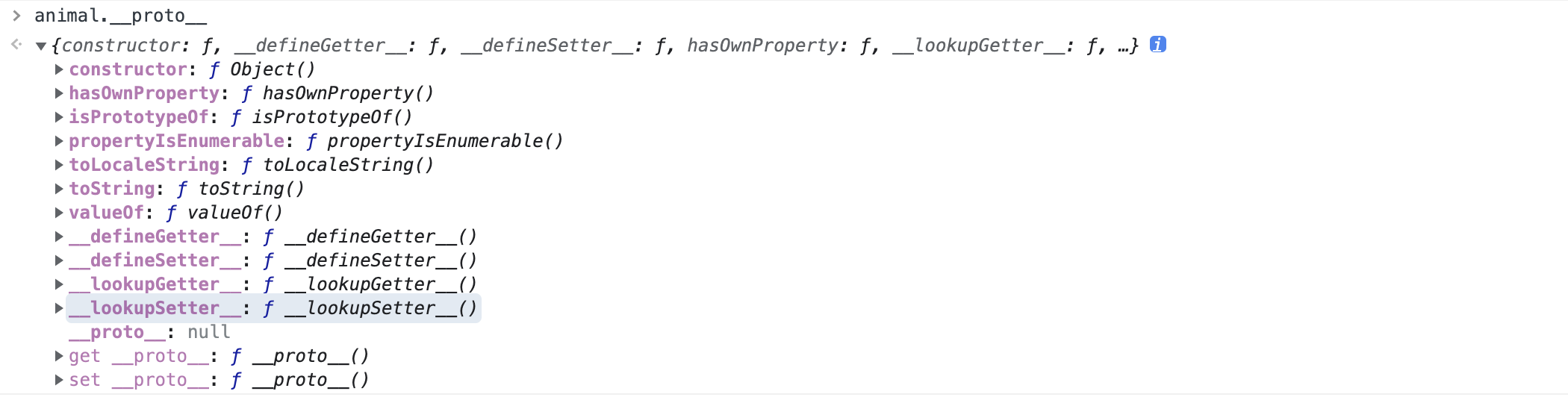

user.__proto__ // {constructor: f User(name)}

user2.__proto__ // {constructor: f User(name)}The new constructed objects' [[prototype]] is an object with a property named constructor, and its value is the constructor function User(name) itself. That’s handy when we have an object and what to know which function creates this object.

What if we want to assign them an existing object as their [[prototype]] so that we don't need to use set object[[prototype]]=object2 to handle them one by one? Luckily, we got a prototypeproperty of a function(constructor) to assign the [[prototype]] object to each object when they are created by the constructor function. However, it should be noted that the prototype property of a function is just a regular property used to set [[Prototype]] for the new object when they are created by the new keyword and constructor function. And the prototype property should be an object or null, other values won't work.

let animal = {

eats: true

};

function Rabbit(name) {

this.name = name;

}

Rabbit.prototype = animal;

let rabbit = new Rabbit("White Rabbit"); // rabbit.__proto__ == animal

alert( rabbit.eats ); // trueSetting Rabbit.prototype = animal literally states the following: "When a new Rabbit is created, assign its [[Prototype]] to animal".

2.4 return to the beginning: Object

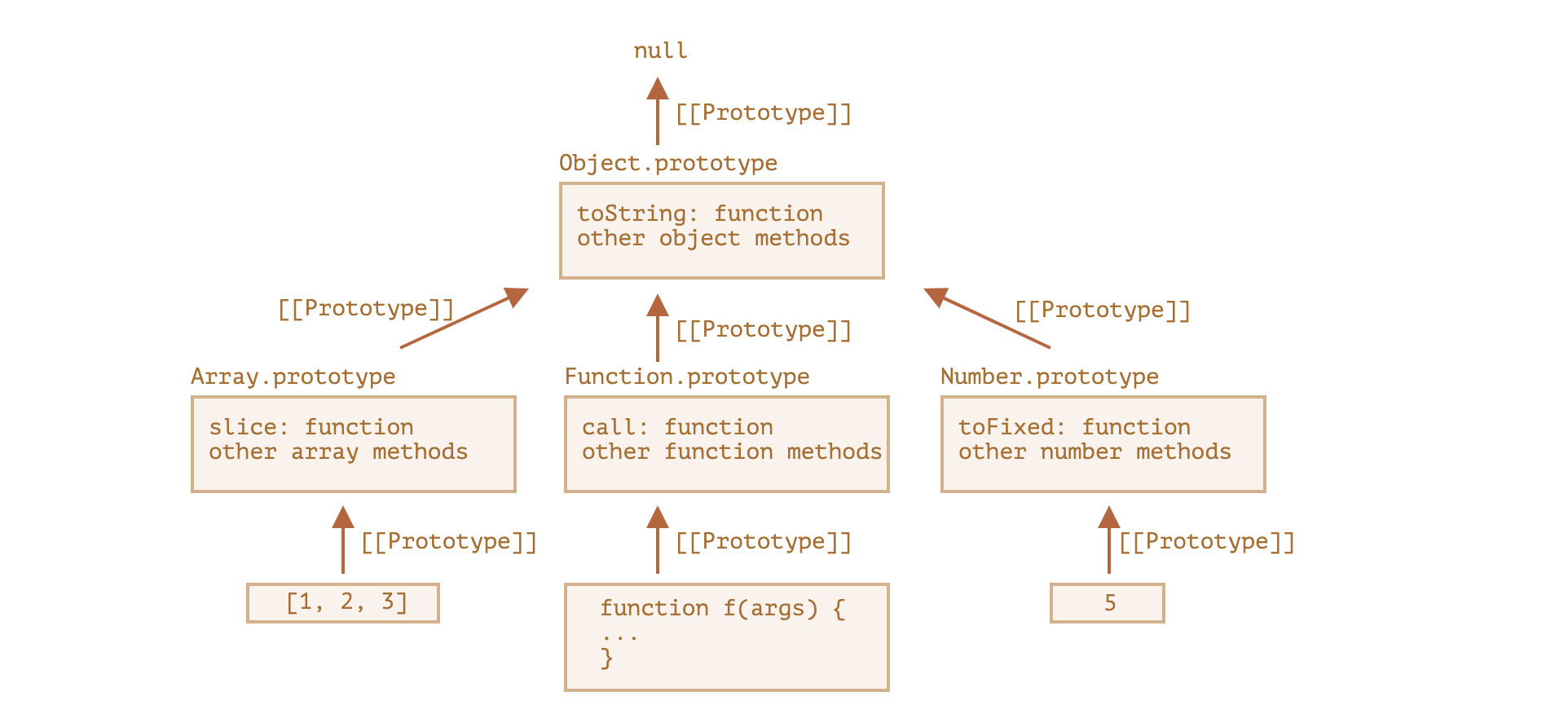

Let's dive in a bit deeper. We have known that an object could get its [[prototype]] by the constructor function's prototype property. And that is also an object and would have its own [[prototype]]. In the above case, what's the [[prototype]] of the object animal?

You will get an object with a lot of built-in functions. And this is because the prototype is wildly used by the core of Javascript.

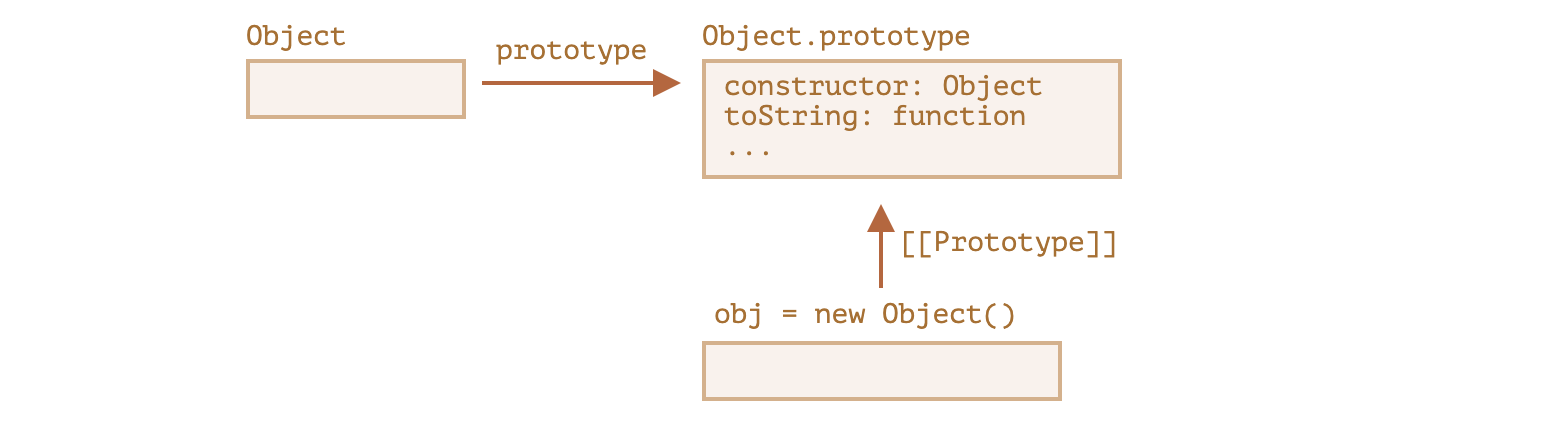

Actually, we define an object like the animal above, the Javascript internally uses a constructor function called Object() to help you create the object. The Object function has the prototype property which contains a lot of built-in functions to support you in interacting with the objects. It can be interpreted that we have created an object in this way: animal = new Object({'eats':ture}).

This is how Javascript works. It is common for us to define an array by using var ary = new Array(). And then, we can use a lot of array methods like ary.length to employ the variable in our code. By specification, Array.prototype provides those methods. We can actually get an actual picture as follows:

What if I set null to an Object's [[prototype]]? You will lose all the built-in methods originally supported by the object.

All built-in objects follow the same pattern:

- The methods are stored in the prototype (

Array.prototype,Object.prototype,Date.prototype, etc.) - The object itself stores only the data (array items, object properties, the date)

And built-in prototypes can be modified or populated with new methods, which might produce vulnerabilities for us to exploit.

2.5 prototype related methods

Object.getPrototypeOf(obj): returns the

[[Prototype]]ofobj.Object.setPrototypeOf(obj, proto): sets the

[[Prototype]]ofobjtoprotoObject.create(proto, [descriptors]): creates an empty object with given

protoas[[Prototype]]and optional property descriptors. However, the descriptors can be used to set properties.

3 Prototype Pollution Vulnerability

I am sorry for paving a lot of stuff of javascript to get here.

When we talk about a new kind of vulnerability, there are two questions that must be clear:

- Where would this kind of vulnerability likely appear? (two levels)

- How can we exploit them?

For the first question, let's summarize the prototype of the Prototype Pollution Vulnerability.

3.1 the prototype of the Prototype Pollution Vulnerability

In a word, prototype pollution vulnerabilities occur in assignment statements where 1. __proto__ shown on the left as the object's key (will be interpreted as the object's __proto__ object) 2. try to assign value to its property (assign to object's __proto__ object itself won't work).

You can try the following cases in the browser's console.

target['__proto__']['toString'] = value; // polluted

target['__proto__'] = {'toString': value}; // won't work

target[key] = {'__proto__': {'toString': value}}; // won't workIn practice, which operations would more likely cause a prototype pollution vulnerability?

- merge objects // from phith0n

- clone objects // from phith0n

- assign(), push(), insert(), extend(), ensureExists(), set(), ...

function merge(target, source) {

for (let key in source) {

if (key in source && key in target) {

merge(target[key], source[key])

} else {

target[key] = source[key]

}

}

}

function clone(obj) {

if (null == obj || "object" != typeof obj) return obj;

var copy = obj.constructor();

for (var attr in obj) {

if (obj.hasOwnProperty(attr)) copy[attr] = obj[attr];

}

return copy;

}3.2 How to exploit?

A usual way is to pollute the Object.prototype object. Since it is inherited by all objects in the javascript, we can inject any properties into the objects and carefully find a place where the properties have been invoked and executed.

At least, prototype pollution vulnerability would lead to a DOS attack. However, if we want to take advantage of prototype pollution to RCE, we still need to find gadgets in the program where an undefined property lookup would take place to land inject commands and then carry the commands to an execution environment.

I would like to find another time to summarize the cases about PP2RCE that I have come across.

Reference

https://javascript.info/getting-started

一张图搞定JS原型&原型链: https://segmentfault.com/a/1190000021232132)

P神的原型链污染漏洞:https://www.leavesongs.com/PENETRATION/javascript-prototype-pollution-attack.html#0x02-javascript

Nodejs与原型链入门CTF: https://www.anquanke.com/post/id/236182